Navigating Democratic Placemaking in Year 2042

Artifact Essay for Colloquim One - Zoe Lin

Setting the Scene:

Post-transactional Street Level Voids

The year is 2042, and gone are the retail spaces that used to line our streets. The declining number of physical retail establishments is a trend in the urban environment that has been well on its way since over a century ago (Kickert, 2022). However, with the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, the shift was accelerated as the market was pushed to innovate new technologies that made online retail both a better experience for consumers and more cost efficient for businesses. This left a real visible impact on our urban fabric, many vacant lots were left in its wake.

As street-level social and economic realities shift much faster than the built stock, these spaces

that used to be storefronts are forced to physically and functionally adapt to new uses. It did not take

long for the city to discover that as our neighborhood experiences are so intrinsically tied to our

relationship to these spaces – as they set the stage to Jane Jacobs’ sidewalk ballet, if you will –

leaving them empty resulted in unhealthy communities and social decay (Jacobs, 1962).

A comparison between a 1911 storefront database of The Hague with that of 2017 demonstrates that about a

fifth of storefronts have changed to a post-transactional use. Many of these new uses have spurred the

creative economy, illustrating the resilient urban value of storefronts beyond merely hosting consumer

transactions (Kickert,

2022).

It became a clear signal that there needs to be a new intervention that anchors us to our physical

environment as society continues to transfer activities like work and school to virtual ones.

New Problem: Democratic Placemaking

While street-level brick-and-mortar stores continue to empty out, our cities were also making great

strides in restructuring their economic systems, implementing socialist policies that supported the

growing population of those whose work sectors have been taken over by machine automation. By way of a

miracle, in the short span of the 20 years, the city found a way to decouple the urban form from its

capitalist economy. This allowed the city to reclaim these voids, and reimagine them as more than just

business spaces that respond to our material and economic needs, and transform them into community co-owned

spaces that answers to social and cultural based needs.

But with this opportunity, came new issues. Without the invisible hand of the market determining

the use of the spaces, the city required a new process of urban decision-making. As money and property

are no longer the basis for civic participation in this post-transactional world, the city had a real

chance to strive for democratic and equitable placemaking.

Inspired by participatory design principles introduced in the 1970s by John F.C. Turner and exemplified in housing projects like Villa Verde Housing, city planners decided that, just as the final use of the voids of these homes are determined by the ones that live in the house, these street level public voids and their uses will be determined by local stakeholders especially since residents can detect the city’s requirements far quicker than administrators can.

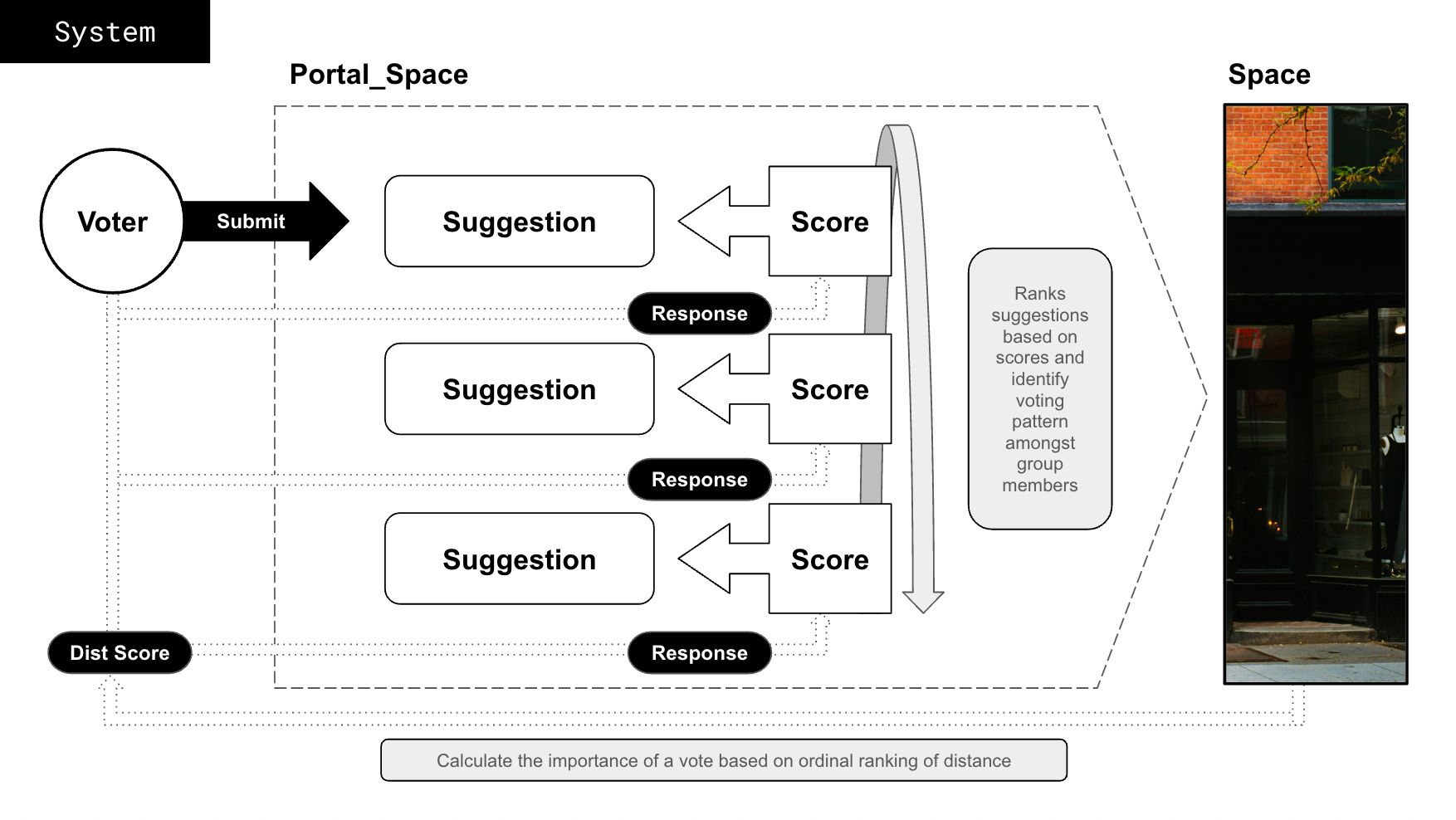

They created a web portal for democratic urban design decision-making that takes geospatial realities into consideration. The system forefronts public choice principles and localism, putting grassroots democracy at work. The portal leverages machine learning’s ability to process large amounts of data to facilitate democratic processes and inform the built environment, creating a process that keeps citizens/users within the loop, allowing them to be designers/developers of their own city, defining their own specifications and needs. This system, paired with the development in modular construction technologies over the years that allowed for quick and easy changes to the built environment for them to meet the requirements of different use cases, made it possible for the city to update these spaces quarterly to flexibly meet the city’s ever changing needs. From galleries to dance studios, music clubs to community gardens, the urban fabric became one that is ever changing.

Portal - “Our Space”: How it works

The portal, refered to as Our Space, serves two primary functions. First, it serves as a way for the

citizens to access a database of all the existing community spaces in the city, and see information

about them, including their current use and the use update date. Secondly, and more importantly, it is

where citizens come together and determine the future use of the space for the next quarter.

The portal is accessible via any device connected to the internet and is also on display on the

digital screens placed at every community owned space.

Every space has a list of suggestions of what the space could become next. Back in 2022, vacant storefronts were already an urban mainstay. But while passersby may dream of what they wish would fill the void, rarely do they get any say in the matter. That is no longer the case. Instead of providing people with options of what the space could become, in a true bottom-up approach, suggestions are completely generated by the citizens to ensure they accurately reflect their wants and needs.

A participatory public art project that explores the process of civic engagement. Inspired by the limited dynamics of community meetings where the loudest people ruled, as well as the volume of abandoned buildings, Chang posted thousands of “I wish this was __” stickers on vacant buildings across New Orleans to invite residents to easily share their hopes for these spaces.

The suggestions are collected simply via a textbox input. The success of the portal is greatly tied to how freeform and open-ended the input of a suggestion is, as it allows the portal to collect and measure the city's collective imagination and cultural value as data. While we’ve developed sophisticated technologies that have been used to calculate and optimize more quantifiable experiences like mobility accessibility or energy management, nothing is more effective in collecting cultural desires and needs by simply asking and allowing people to speak.

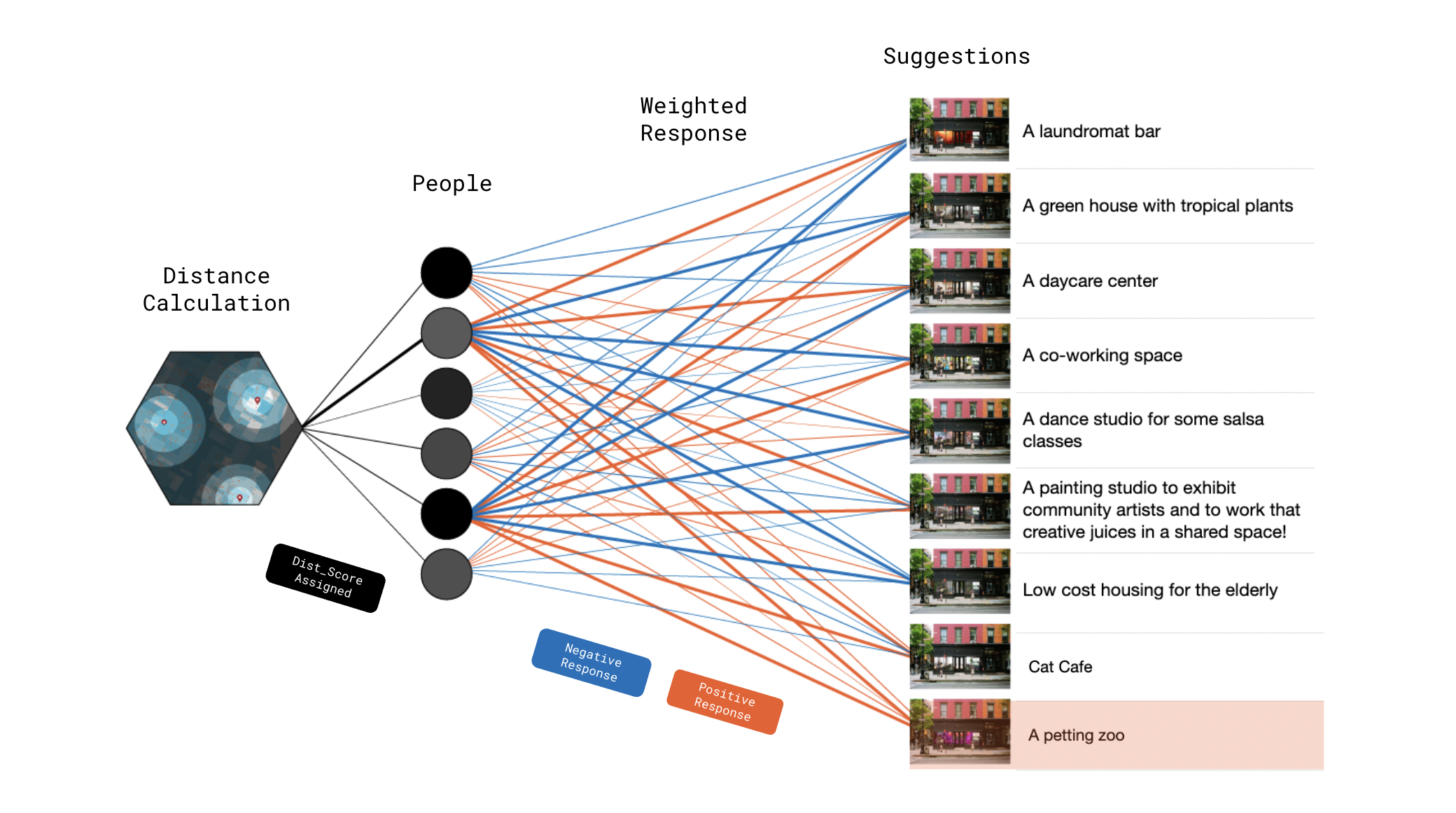

These suggestions are then ranked by a simple equation:

suggestion_score = ⅀(response*dist_score)

Processing open-ended data collection and the massive amount of resulting text used to be a hefty

task before the age of artificial intelligence. Taking a page out of Polis’s book, a survey tool that

combines crowd behavior and machine learning, Our Space encourages participants not only to provide

suggestions, but also provide responses to other suggestions by agreeing and disagreeing with them,

generating a rating of sorts.

However, not all opinions on a space should be considered equal. For example, a person who lives

directly above a space should have say garding the use of that space than someone who lives a 30

minute commute away. The system recognizes the importance of forefronting

localism and empowering local stakeholders as they are those that the spaces serve most and can best

identify district-specific needs with most accurately.

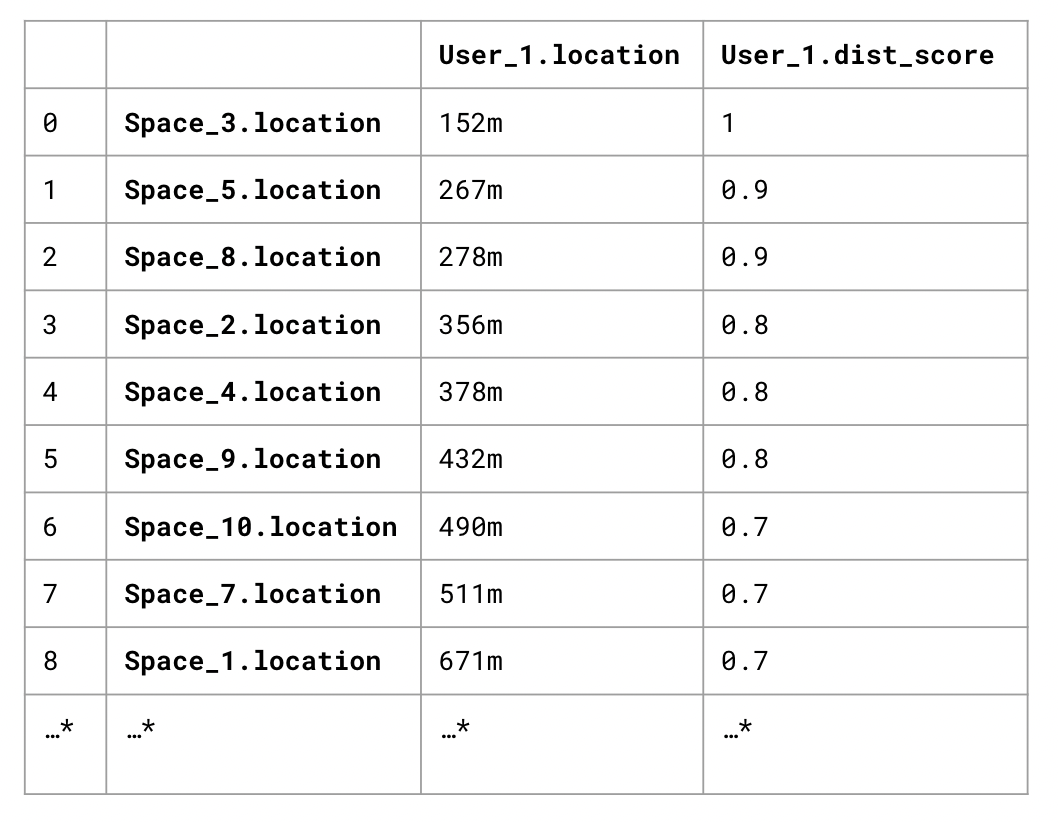

Our Space takes this into consideration by having every user create an account tied to their current

primary address. The importance of a vote is based on the distance between a user’s residence and the

vacant spot, their response is weighted by a distance score. These distance scores are assigned based on

an ordinal sorting of the participant’s relationship to the space from the participants’ perspective.

That is to say for every user, Our Space calculates their distance between all the spaces in the city

and ranks them from closest to furthest. Based on the order of ranking, the distance score a given user

has for the space is assigned from 1 to 0.1. So if two users share the same closest space, they both

have a distance score of 1 that weighs their responses to suggestions associated with the space,

regardless of how far they actually live from the space.

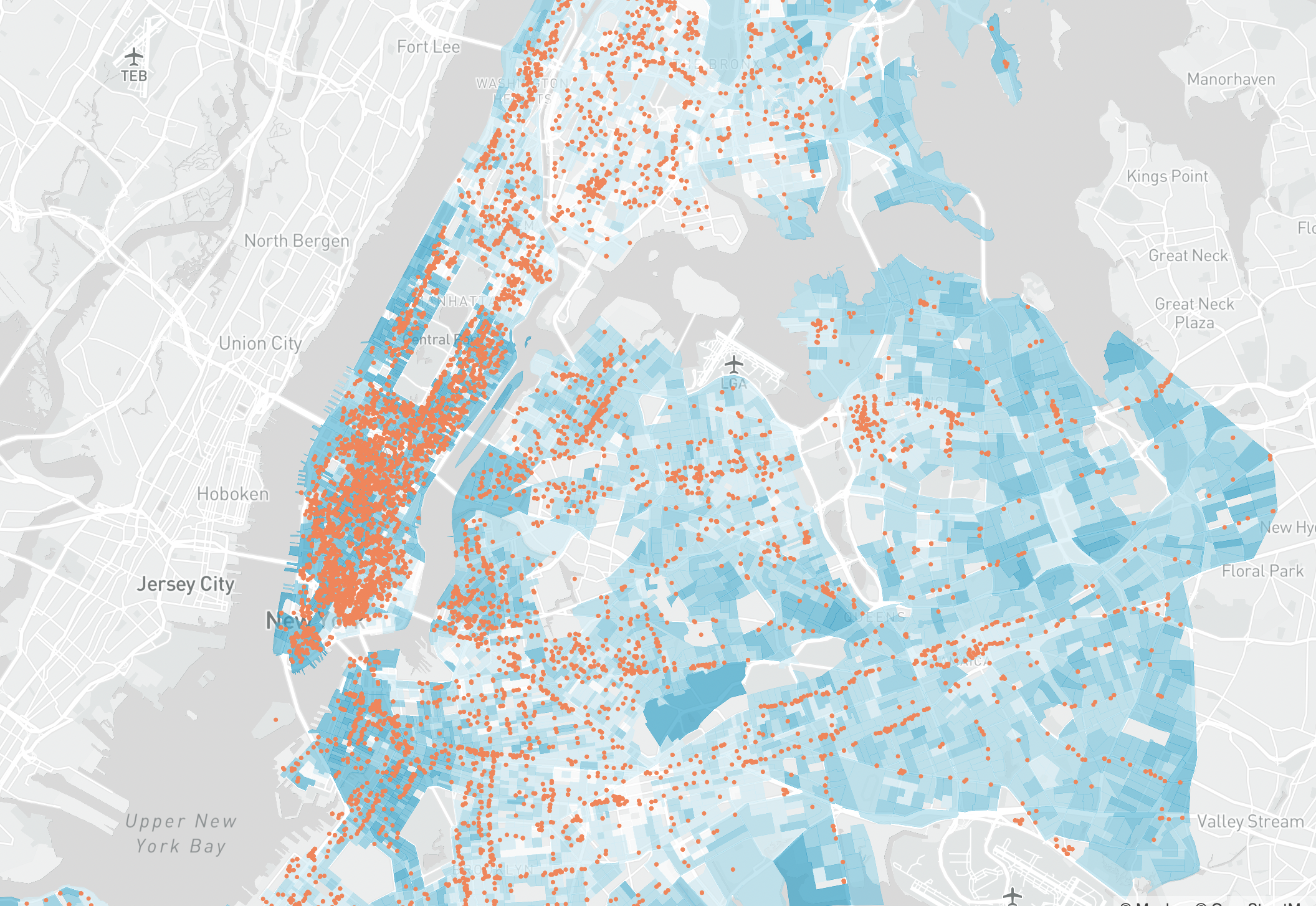

This is to address the fact that while the program strives for democratic and equitable placemaking,

the location of the built stock was informed by market potential for retail, resulting in an uneven

spread. It is unsurprising that the density of these storefront locations are correlated with the Median

House Hold Income of the neighborhood.

While ensuring people have equal access to spaces is a goal the program is working towards, the

ordinal assignment of distance score intends to take these geospatial realities into consideration and

ensure everyone has an equal voice within the program.

What this results in is a matrix of suggestions and users for each space with a response in each cell, allowing us to rank suggestions based on scores and identify voting patterns amongst group members by clustering them. The resulting data is then used to determine the use of the space in the coming quarter and is also used to report to city planners a summary of the types of cultural value and cultural subgroups that exist in the area, giving them data to better evaluate and support a community’s potential wants and needs.

Implications: Endless Questions

What does this particular algorithm look like? Something questions I am particularly interested in is whether the urban

configuration that emerge from such a system have different types of uses be evenly distributed? Or will people with

similar cultural desires start clustering? Caught within this feedback loop of moving towards areas that provide

services they enjoy determined by the people from the area and voting for more similar services. If such is the case,

what are the implications of this clustering, a strong local cultural identity that is welcomed? Or bubbles of cultural

self segregation and a more divided society that embedded and reflected spatially? Is this truly equitable? Within

theses bubbles, how do we ensure minority needs are heard when the algorithm favours the majority, can we encapsulate

rules within it that protects baseline needs? Or can we trust that as these spaces update use cases in intervals, it

will self organize based on community feedback to have different types of uses be evenly distributed?

These questions are currently beyond the scope of this project, but are certainly things I would like to continue to explore.